My keyless car got stolen, so I worked out how they did it

On December 2024, I had my keyless car stolen from my house. Understandably, I was distraught. I spent many months pondering how it could have happened and what made my car the ideal victim? After some research, and actually coming into possession of the vehicle after four months of it being lost in the abyss, I was able to piece together the puzzle. In this post, I hope to bring awareness to the security of modern vehicles, attacks that are actively being exploited, and ways a driver can protect their car from such exploits.

Since my own incident, may more keyless cars have been targetted, but why exactly?

While the perpetrators definitely "plugged a computer into my car and emulated the fob signal", my aim for this post is to perform a complete technical deep-dive into the science behind these vulnerabilities and the attacks associated with them (with pictures!).

What is Remote Keyless Entry?

This access control mechanism is called a Remote Keyless Entry (RKE), or Passive Keyless Entry and Start (PKES) system. It can be found in many cars brands such as the Suburu WRX, and the Holden Commodore, and is honestly not uncommon. Unfortunately, such a system is fallible to exploits (as is any system). As Victorian vehicle theft statistics [1] suggest, this is a very lucrative and simple-to-execute exploit. The RKE system initially contained infrared technology, outlined in the patent by Paul Lipschutz [2]. This was adapted onto the Renault Fuego and thus began the integration of technologically advanced key fobs over traditional physical keys.

While traditionally infrared-driven, key fobs these days rely on radio frequencies which have the ability to communicate with a vehicle in a range of 10-20 metres [3]. This kind of remote keyless entry system typically contains the remote entry system, a mechanical locking alongside a key blade, and finally, an RFID-enabled immobiliser [4]. This immobiliser is utilised to authorise the key fob and start the engine once it is inside the car [5]. The key blade is inserted an acts like a traditional key although it is not require to open the vehicle.

Amplitude Shift Keying (ASK) and RF Communication

Amplitude Shift Keying (ASK) modulation is used for the physical wireless signal, wherein smaller devices work on Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) modulation. The frequency depends on the regulation, standards, and regions. In Australia, most vehicles operate on 433.92 MHz, the same frequency used across Europe and much of Asia. This falls under the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) regulations for Low Interference Potential Devices (LIPD), which govern short-range devices including car key fobs [6]. Some imported vehicles, particularly older models from North America, may operate on 315 MHz, though this is less common in the Australian market.

The traditional RKE transmitter sends a command with a preamble, an identifier, the encrypted data field, and an integrity check field such as a Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC). To achieve security against possible thefts, the RKE system implements integrity protection mechanisms such as Message Authentication Code (MAC) and authentication. In general, the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) follows the international ISO/SAE 21434 standard for security guidelines of these devices [7], where specific aspects and requirements for RKE systems dictate the design, implementation, and maintenance of a secure system.

Attack Vectors

The sophistication of keyless car theft has evolved dramatically over the past decade. What started as simple relay attacks has expanded into a multi-faceted threat landscape. As such there are many different types of attacks that are used.

Relay Attacks

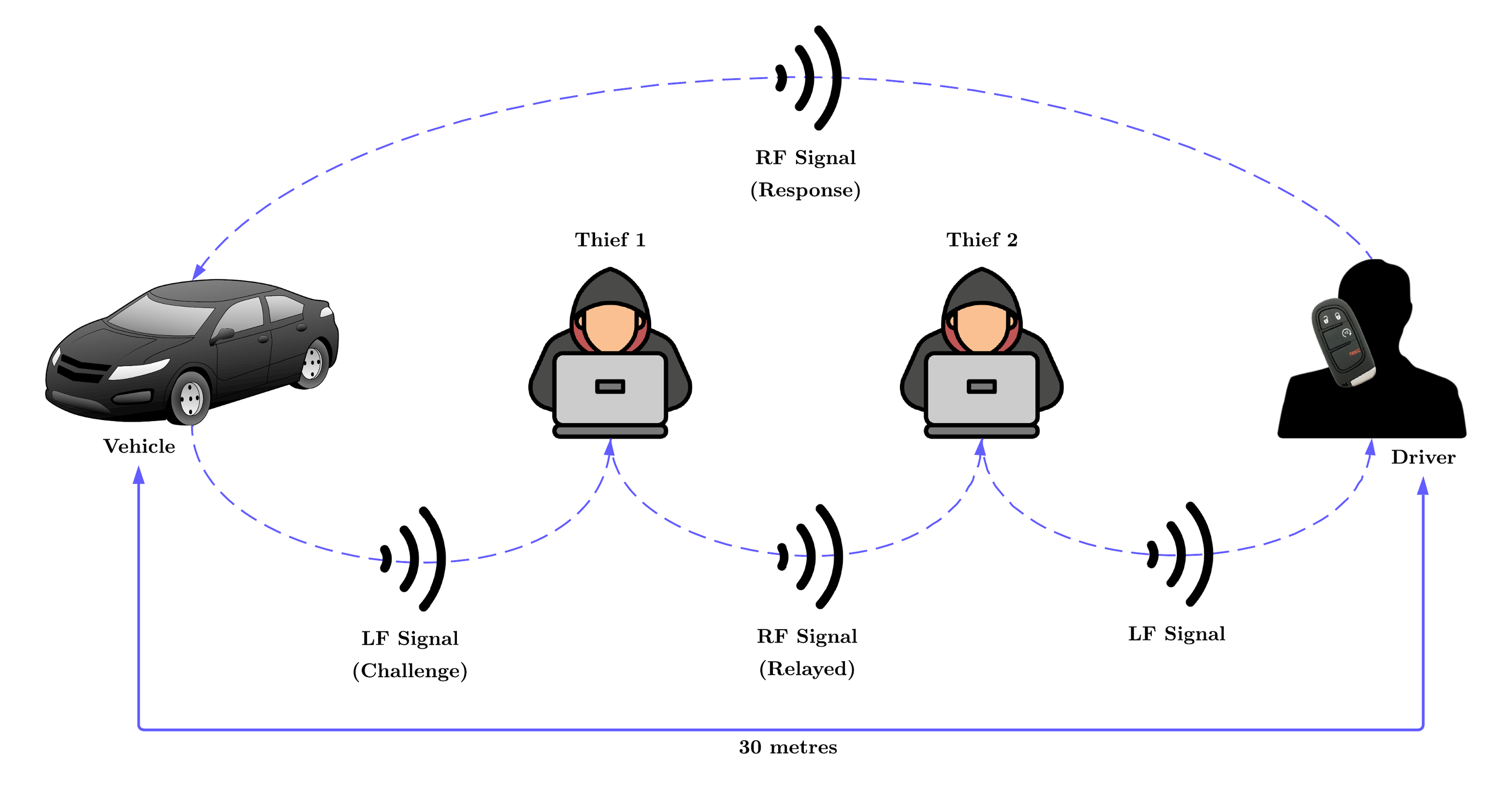

The relay attack is the most prevalent method used by thieves today. This attack exploits the constant low-frequency signal emitted by passive keyless entry systems, working through signal amplification and relay between two devices operated by two thieves working in tandem.

The attack begins with the first individual, who stands near your house (often near a window or door where RF signals penetrate more easily) with a relay amplifier device. This device detects and boosts the weak radio signal from your car key, even if it's inside your pocket, handbag, or on a hallway table. The amplifier captures the key's unique signal and relays it to the second device. Some commercial relay devices can pick up signals from over 100 metres away.

The second individual stands next to your car holding a transmitter. This device receives the boosted signal from the first device and tricks your car into thinking the key is right next to it. The car's security system, believing the legitimate key fob is present, unlocks the doors and allows the engine to start.

What makes this attack particularly insidious is that it doesn't break any encryption or cryptography. It simply extends the communication range between the legitimate key fob and the vehicle. The car receives genuine, authenticated messages from the real key, just relayed from a distance. This is why traditional rolling code protections offer no defense against relay attacks [5].

CAN Bus Injection Attacks

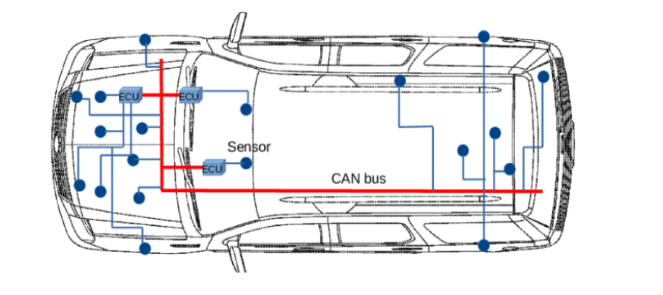

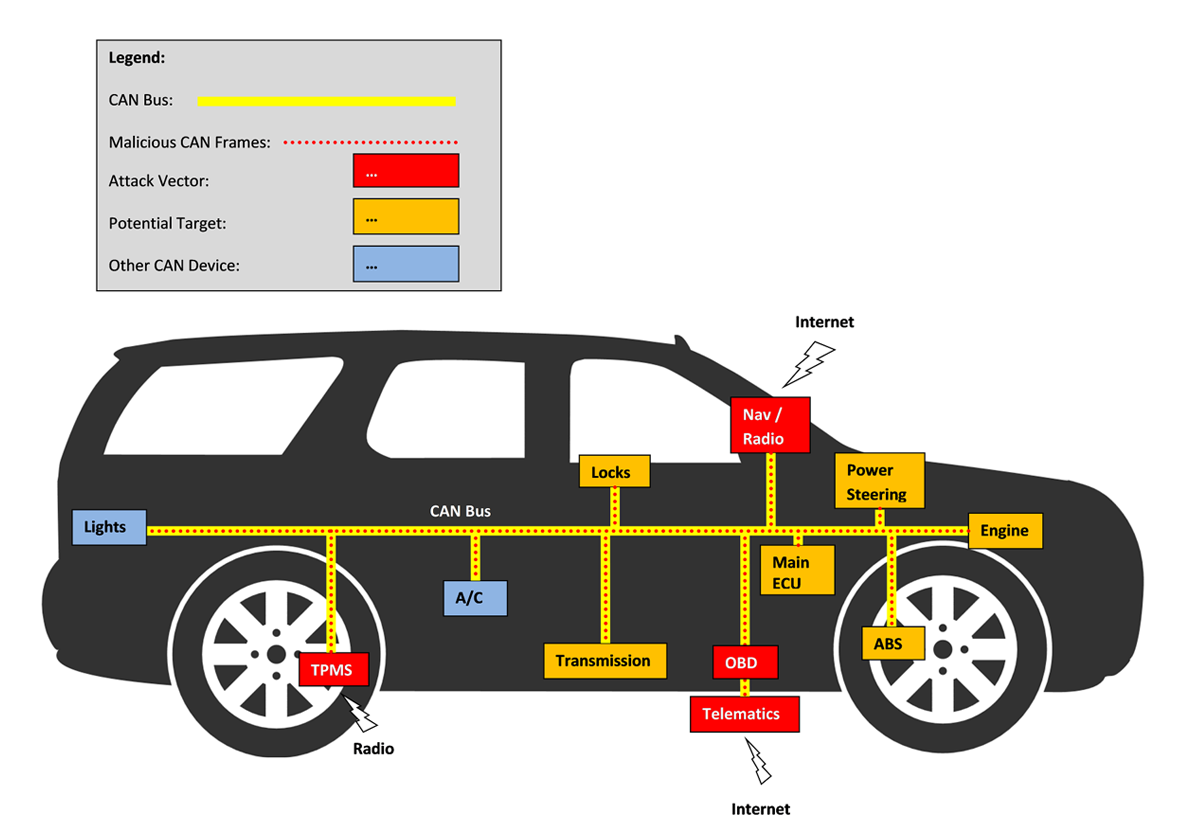

When relay attack countermeasures became more common (Faraday pouches, keys with sleep modes), thieves evolved to a more sophisticated method known as CAN Bus Injection. This attack bypasses the entire smart key system by directly manipulating the vehicle's internal communication network.

The Controller Area Network (CAN) bus is the central system of modern vehicles. It's a message-based protocol that allows various Electronic Control Units (ECUs) throughout the vehicle to communicate with each other. Every action in the car, from unlocking doors to starting the engine, is controlled by messages sent across the CAN bus. The CAN Injection attack typically targets accessible points where the CAN bus wiring is exposed. In some vehicles, thieves have accessed CAN wires behind headlamps by pulling apart the housing and unplugging cables. Once connected, the attacker injects forged CAN messages that mimic commands from legitimate ECUs.

Once access is gained, the CAN Injector sends a CAN frame to wake the CAN bus from sleep mode, similar to what happens when a door ECU detects activity. The device then floods the CAN bus with messages declaring "a valid key is present" or directly instructing actions like unlocking doors and disabling the immobiliser. Advanced CAN Injector devices use a technique called "dominant-override" where they can force their messages to take priority over legitimate ECU messages, effectively taking control of the vehicle's systems.

This attack succeeds because traditional CAN bus implementations lack authentication. The system was designed for a closed, trusted environment where all ECUs were assumed to be legitimate. If you can inject a CAN bus signal via accessible points like headlights, you can effectively control anything [8]. Modern manufacturers are addressing this with SecOC (Secure Onboard Communication) which implements cryptographic message authentication, but the first cars using SecOC have only been on the road for two or three years, leaving millions of older vehicles vulnerable.

OBD-II Port Exploitation

The On-Board Diagnostics (OBD-II) port, mandated in all vehicles manufactured after 1996, provides standardised access to vehicle systems for maintenance and diagnostics. Unfortunately, this port gives direct access to the vehicle's internal networks and ECUs, and if not secured, allows for malicious reprogramming.

Using affordable scan tools, thieves can program a new key fob in minutes. Black-market "emergency start" modules can be plugged in to defeat the engine immobiliser. The OBD-II port exposes CAN High and CAN Low lines (pins 6 and 14), allowing direct message injection into the vehicle's communication network.

Newer vehicles implement security gateways between the OBD-II port and critical CAN buses. These gateways act as firewalls, allowing only specific pre-configured diagnostic messages through and requiring authentication as an authorised diagnostic tool. However, many vehicles on the road lack these protections, leaving them vulnerable to OBD-II based attacks.

Rolling Code Attacks

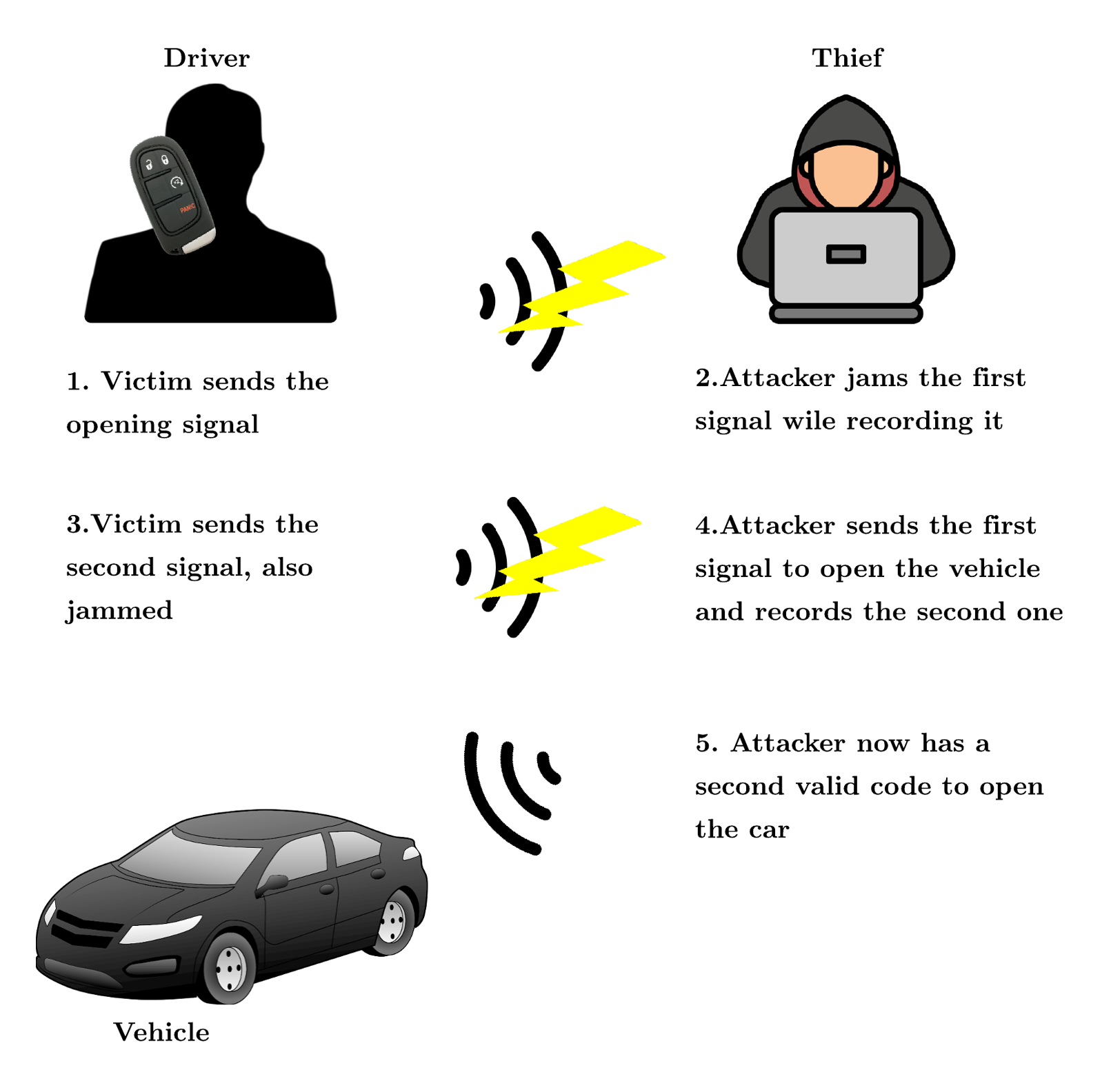

Rolling codes were introduced to prevent simple replay attacks. Each time you press your key fob, it generates a new encrypted code using a counter value. The car expects codes in sequence, and old codes are rejected. KeeLoq rolling code, one common implementation, utilises a 66-bit transmission code, of which 32 bits are encrypted, providing almost 4 billion possible code combinations. The receiver maintains a list of up to 1,000 future valid passwords to handle button presses when out of range.

Despite this protection, the RollJam attack defeats rolling codes through signal jamming and code capture [9]. When a driver presses unlock, the attacker jams the signal and captures the code. The car doesn't unlock because the signal was jammed. When the driver presses unlock again in frustration, the attacker jams and captures this second code as well. The attacker then transmits the first captured code to unlock the car, making the driver think their second press worked. Later, the attacker can use the still-valid second captured code to unlock the car again at their leisure.

A newer variant called RollBack exploits resynchronisation features in rolling code systems. By capturing signals only once, the attack can be exploited at any time in the future as many times as desired, with analysis showing approximately 70% of tested vehicles are vulnerable to this technique.

Signal Jamming and Blocking

Signal jamming uses portable radio jammers to overwhelm the key fob's signal when the owner tries to lock the car. The owner presses "lock," hears no confirmation, but assumes the car locked anyway. The jammed command never reaches the vehicle, leaving it unlocked for easy content theft or OBD-II port access. This attack is particularly effective in crowded parking lots where owners might not notice the lack of confirmation beep or light flash.

Bluetooth and Ultra-Wideband Vulnerabilities

Modern vehicles, including Tesla models, are moving toward Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and Ultra-Wideband (UWB) for keyless entry. However, even these newer technologies have proven vulnerable. Tesla Model 3 and Model Y vehicles have been demonstrated to be susceptible to BLE relay attacks, allowing thieves to unlock and drive away in seconds if advanced security features like PIN-to-drive are not enabled.

Although Tesla's systems support UWB technology, which offers precise distance measurements that should theoretically prevent relay attacks, the vehicles primarily still use Bluetooth to unlock cars and control immobilisers. This means relay attacks remain successful against these vehicles. UWB implementations are still maturing, and until they become the primary authentication mechanism rather than a supplementary feature, the vulnerability window remains open.

So, how can I protect my vehicle?

Given the sophisticated nature of these attacks, a layered security approach is absolutely essential. Physical barriers remain surprisingly effective despite their low-tech nature. A steering wheel lock is quite old-school but provides a visible deterrent that adds time and complexity to any theft attempt. For the OBD-II port, a dummy port can be installed with the real one relocated elsewhere in the vehicle, using a lockable OBD-II port cover, or installing an inline switch on critical lines like BUS+, CAN High, and K-Line. Some manufacturers now offer protective shields for CAN-accessible components like headlight and taillight assemblies.

Faraday pouches or boxes store key fobs in signal-blocking containers that prevent RF communication entirely. The location where you keep your keys matters significantly, so keep them deep inside your home, away from exterior walls, and doors where signals can more easily reach. Many modern key fobs now include sleep modes or the ability to disable passive entry features when not needed, which you should enable whenever possible.

Ghost immobilisers are secondary immobiliser systems that require a unique PIN code before the vehicle can start, providing a form of two-factor authentication for your car. Aftermarket CAN/LIN immobilisers can be installed to authenticate legitimate commands on the vehicle's communication bus. For vehicles that support it, like Tesla models, enabling PIN-to-drive provides multi-factor authentication that can thwart even successful relay or BLE attacks. GPS tracking systems won't prevent theft but significantly increase recovery chances if your vehicle is stolen.

Beyond specific security devices, adopting certain practices makes a substantial difference. Always verify your car is actually locked by listening for the lock mechanism and watching for mirror folding or other confirmation signals. Be aware of your surroundings, as thieves often scout target vehicles days in advance, looking for patterns and vulnerabilities. Park strategically in well-lit areas, use garages when possible, and consider parking close to obstacles that limit access to certain parts of your vehicle. Finally, inform your insurer about security measures you've implemented, as some offer premium discounts for enhanced vehicle security.

The State of Manufacturer Response

Manufacturers have known about these vulnerabilities for years, but developing and implementing security technology on production lines is a costly process taking many years. The automotive industry began taking these threats seriously following the famous 2015 Jeep Cherokee remote hack demonstration, which showed that modern vehicles could be compromised remotely while driving on the highway.

Current responses include the implementation of SecOC (Secure Onboard Communication), which adds cryptographic message authentication for CAN bus communications. Motion sensors in key fobs now allow keys to enter sleep mode when motionless, preventing relay attacks when the key is stationary. UWB technology promises more accurate distance measurement to prevent relay attacks, though implementation remains incomplete in most vehicles. Over-the-air update capabilities allow security patches to be deployed without requiring dealer visits, enabling faster response to newly discovered vulnerabilities.

Final Thoughts

The theft of my vehicle was a horrendous wake-up call to the realities of modern automotive security, an aspect of security I had never thought about prior. While manufacturers tout convenience features like keyless entry and push-button start, these systems were designed with usability, not security, as the primary concern. The CAN bus, for example, was never intended to be a security boundary, it was designed for a trusted, closed environment where all components could be assumed legitimate.

What's particularly concerning is the democratisation of these attack tools. What once required specialised knowledge and custom hardware can now be accomplished with devices available on e-commerce platforms. The barrier to entry for automotive theft has never been lower, and the techniques continue to spread as criminals share knowledge and tools.

The solution requires collaboration between manufacturers, regulators, and consumers. Manufacturers must prioritise security in vehicle design, implementing defense-in-depth approaches rather than relying on single security mechanisms. Regulators need to enforce minimum security standards and perhaps even mandate regular security audits for critical vehicle systems. Consumers must educate themselves about vulnerabilities and take proactive protective measures rather than assuming their expensive modern vehicle is inherently secure.

My car was eventually recovered, but not before it had been thrashed around for 10,000kms in four months, and used in who knows what activities. The financial cost was significant, but more impactful was the violation of security and the realisation of how easily modern vehicle security can be circumvented. By sharing this technical analysis, I hope to raise awareness and encourage both individual action and systemic change in automotive security practices. The technology that makes our lives more convenient should not come at the cost of making our property more vulnerable.

References

- [1] Crime Statistics Agency Victoria, “Recorded offences,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/crime-statistics/latest-victorian-crime-data/recorded-offences-2

- [2] P. Lipschutz, “Remote control door lock,” U.S. Patent 4,258,352, Mar. 24, 1981. [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4258352A/en

- [3] Car Key Leicester, “How far away do car keys work?” [Online]. Available: https://carkeyleicester.co.uk/how-far-away-do-car-keys-work/

- [4] “Lock patent,” U.S. Patent 1,300,150, Apr. 15, 1919. [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US1300150A/en

- [5] A. Francillon, B. Danev, and S. Čapkun, “Relay attacks on passive keyless entry and start systems in modern cars,” in Proc. Network and Distributed System Security Symp. (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, Feb. 2011. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2995289.2995297

- [6] Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), “Low interference potential devices (LIPD) class licence.” [Online]. Available: https://www.acma.gov.au/licences/low-interference-potential-devices-lipd-class-licence

- [7] ISO/SAE 21434:2021, Road vehicles — Cybersecurity engineering, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- [8] K. Tindell, “CAN injection: Keyless car theft,” Apr. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://kentindell.github.io/2023/04/03/can-injection/

- [9] S. Kamkar, “Drive it like you hacked it: New attacks and tools to wirelessly steal cars,” presented at DEF CON 23, Las Vegas, NV, USA, Aug. 2015.